Full Title:

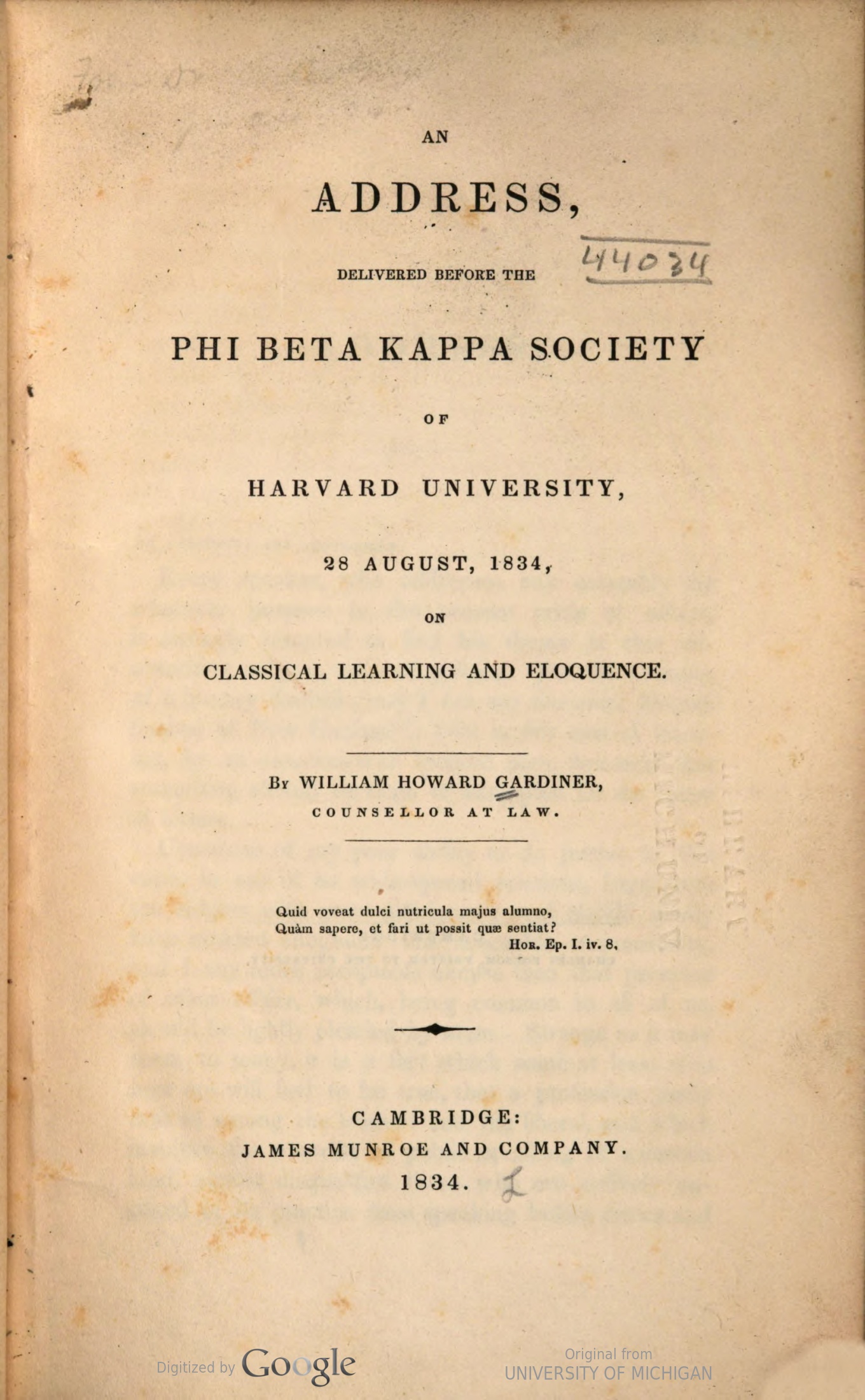

An address, delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa society of Harvard university

Excerpt:

MR. PRESIDENT AND GENTLEMEN :

Every speaker, who addresses any assembly for whatever purpose in the present crisis of affairs, is strongly tempted to find his theme in that all absorbing subject, national politics. But the occasion of a literary festival (may I not say the chief literary festival of New England 7) held in this seat of learn ing, by an association of lettered men, demands that something should be done or attempted for the cause of letters.

Conscious of my poor ability to do justice to this cause in any of its wide-spread relations, I approach the subject with great diffidence ; and should gladly have avoided altogether this honorable responsibility, had I any more acceptable excuse than that pressure of other affairs, which, being common to all of us, should be lightly pleaded by none. Strange as it may seem to many, it is a fact which some at least who hear me will feel to be true, that a profession justly ranked among the learned and the liberal, and which involves the exercise of public speaking of a certain kind, almost disqualifies those who are actively engaged in its practice from speaking before critics and I men of letters on the great questions of literature and philosophy. In the more elevated walks of the legal profession, how engrossing and exclusive are its pursuits And as it is actually practised among us, with no division of its manifold labors, it were difficult for any but a lawyer to conceive how much of this liberal and glorious art is merely mechanical; — how much of life is wasted in the drudgery of forms, and how much in the hard study of trivial facts, a species of learning not deserving the name of knowledge, and which, when once used, we are studious only to forget. Years so spent may sharpen the faculties; but they neither fill nor elevate the mind. Men thus occupied can not, or at least ordinarily do not, keep pace with the literary progress of the world. They turn their thoughts habitually into no such channels. Nor is this the worst. The more elegant acquisitions of youth are, alas ! too often neglected and too soon forgot ten. All the bright trains of ideas, rich as a Roman triumph, which were wont to rise spontaneously in the mind freshly filled with classical associations, exhilarated by the noble sentiments, warmed by the poetic imagery, and inspired by the godlike eloquence of antiquity, will be found to have fled, like a dream, with the habits which produced them, and the very memory of the materials out of which they were formed. Whenever, therefore, a practical lawyer shall have been induced by your call to quit the forum for this place, more appropriate to scholars and men of literary renown, it would be wise in him, not to depart more widely from the usual forensic track than the occasion may absolutely require.

Source Citation:

Gardiner, William Howard. 1834. An address, delivered before the Phi beta kappa society of Harvard university, 28 August, 1834, on classical learning and eloquence. Cambridge: J. Munroe and Company. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001449993