by Liza Ann Bolitzer, Kean University

Learning Objectives

This teaching module aims to increase student’s ability to:

- Employ historical thinking in exploring decision-making in qualitative research.

- Identify ethical relationships between researchers and study participants, including changes to those relationships over time.

- Engage in processes of content analysis within qualitative research.

Introduction

A common initial misconception for students learning about qualitative research in the social sciences is that there is one single correct way to conduct research. Students often begin their methods courses looking for specific instructions—use this model with this number of participants and these data collection methods—and are surprised to learn that qualitative research is an iterative process of decision-making with no clear right answers.[1] Students are, furthermore, unaware of the complex history of research methods and how the processes and goals of qualitative research continues to develop today, especially in terms of the relationship between researchers and participants.[2] A key objective of these courses is, therefore, to teach students how to make complex decisions within qualitative research, thereby positioning them, as novice researchers, to become the key instruments of their studies.[3] This teaching module aims to address this aim within an introductory doctoral course in qualitative research.

This teaching module draws on the epistemological approach of historical thinking that views the past through an empathetic lens. Historical thinking calls on us to see people and their actions as occurring within, at times, contradictory social currents, which yielded complex responses.[4] As Wineburg states, historical thinking “teaches us to go beyond our brief life, and to go beyond the fleeting moment in human history into which we’ve been born.”[5] Such a viewpoint, of making imperfect decisions within particular contexts, is also central to the work of qualitative researchers who are tasked with making complex ethical and methodical decisions within varied contexts.[6] The hope is that by learning to extend an empathetic lens to researchers within the content analysis of historical research documents, students will learn to extend the same grace to themselves as novice researchers; that they will learn to enact reflective and thoughtful research practices rather than search for correct answers.

This teaching module is designed for use in a master’s or doctoral introductory course on qualitative methods within a college of education. It could, however, be adapted for use in anthropology or sociology courses, which often include a focus on the history of those fields. It may also be adapted for other courses that employ a historical lens to teach about changes within and across disciplines over time. For example, interdisciplinary courses that include attention to development of forms of inquiry within and across disciplines. And lastly, it could be adapted to history courses that teach students to engage in historical research and include changes to those methods over time. It is designed for either face-to-face instruction or online synchronous discussion, as both formats can facilitate the in-depth discussion necessary to processes of inquiry.[7]

Summary of Activity

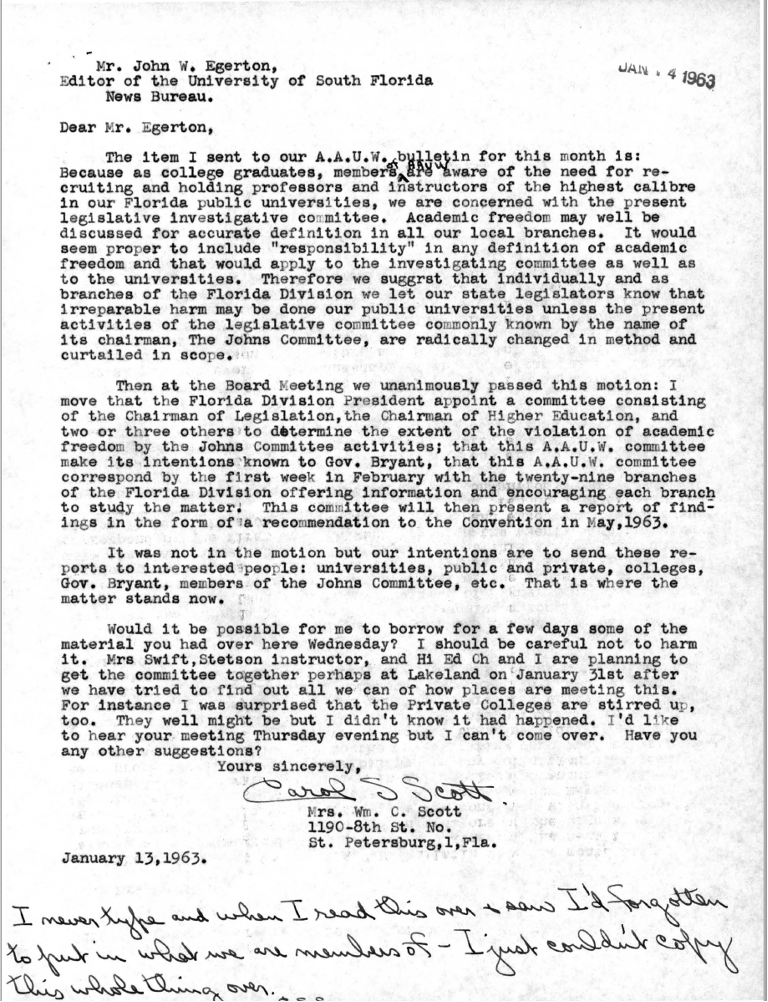

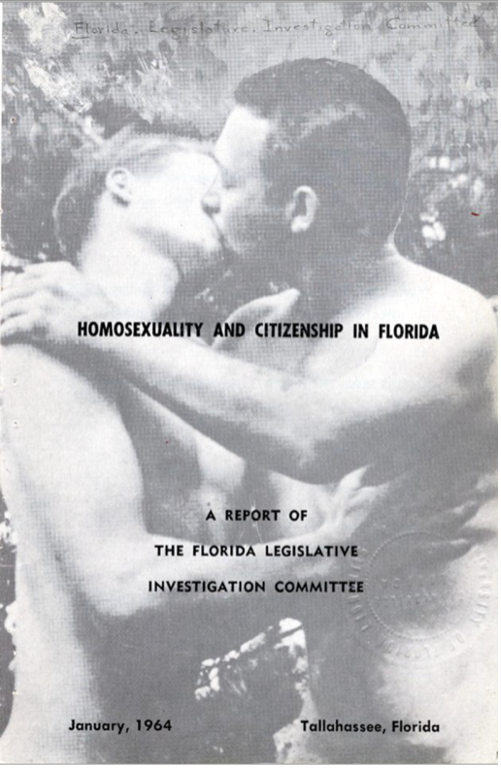

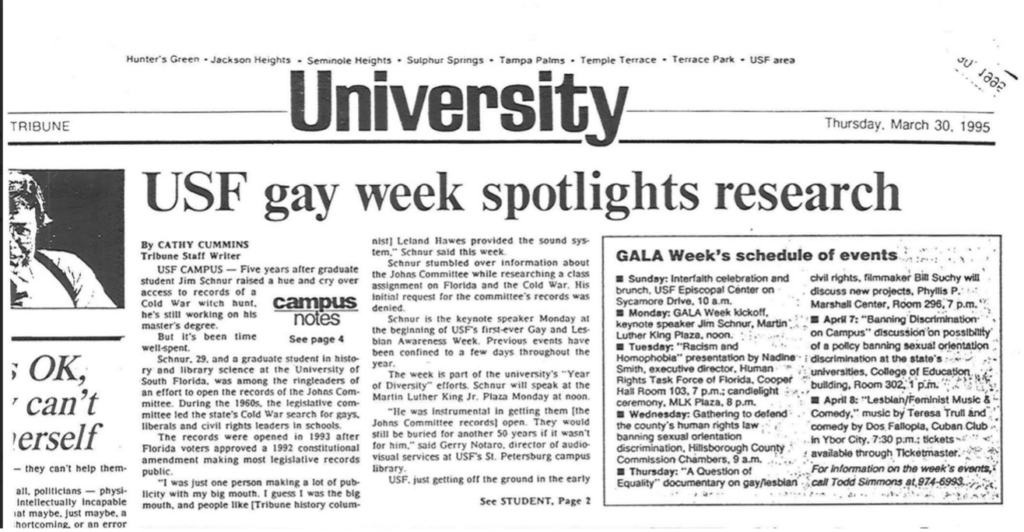

This teaching module leads students in analyzing artifacts of prominent researchers (e.g. letters, observational notes, analytic memos, interview transcripts, etc.) to develop students understanding of ethical decision-making in qualitative research.[8] After a brief pre-activity on the history of research traditions, students work individually and in groups to examine the research processes of a prominent researcher from the past: Margaret Mead, Ernest Burgess, W.E.B Du Bois, or Abraham Flexner. They will then draw from what they observe in the artifacts to explore decision-making in qualitative research and the relationship between researchers and study participants.

Materials:

The materials for this activity are collected on the following site: Teaching Qualitative Research Through Historical Thinking

Breakdown of Activity

Estimated Time: 2 Hours

Pre-Activity: Situating Students

- Opening Exercise: Definition of terms.

- Break students into small groups. Ask groups to define the following terms:

- Culture

- Social systems

- Break students into small groups. Ask groups to define the following terms:

- Present a mini lecture on anthropology and sociology as roots of contemporary qualitative inquiry in education. In this lecture, emphasize the shared goal of these disciplines—to better understand the forces that shape peoples’ lives, and the meanings people make of those forces—as well as their distinct aims. Draw from students’ definitions of culture and social systems, emphasizing how different forms of data collection, such as interviews, observations, surveys, and content analysis, were employed to study each.[9]

Part 1: Examining Primary Sources

- Divide students into 4 groups and assign each an early researcher.

- Margaret Mead

- Ernest Burgess

- W.E.B Du Bois

- Abraham Flexner

- Students look individually at materials for their assigned researchers.[10]

- Students spend five minutes individually reviewing the range of materials under their assigned researcher. Each student then selects one item for their researcher which displays the research process in some way.

- Students complete a “Looking Form” for the piece that they chose.[11]

- Students share the item they selected for their researcher with group members.

- Instructor circulates, listening as students talk in groups or work individually. If needed, help students analyze the primary sources and answer questions about the researchers and the artifacts. Notes student comments and questions to draw from in the second part of the activity.

Part 2: Class Discussion

- Discussion for Understanding: Instructor projects student responses to the Looking Form on the board and invites them to share their responses. Instructor writes a list of decisions the students observed in the artifacts on the board or a shared document, situating those decisions within the major stages of the research process (design, data collection, analysis, and presentation).

- What are you seeing?

- What are you wondering about?

- What decisions do you see the researchers making?

Discussion for Research Practice: Instructor facilitates a whole class discussion of each researcher’s relationship to their participants using the following questions and mapping students’ responses on the board. At the end of the discussion, look at the board with the class, emphasizing what students were able to see—or not see—within the primary sources. Emphasize what they identify as ethical practices that they value in qualitative research.

- What do you notice about the researchers’ relationships with their participants?

- What research practices do you see that you would want to apply in your work? Why?

- What research practices would you not want to employ? Why?

- Closing Reflection: Five minute free-write. What did you learn today about doing qualitative research? What are you still wondering about?

Wrap-up/Transition

- Implications for Educational Research: Building on students’ responses, discuss points of agreement and disagreement in for educational researchers. How has the field changed over time? How has the development of reflective practices in research supported that growth?

- Educational Research as a Field

- (Often) located in schools of education

- Educational researchers draw from multiple disciplines, such as psychology, sociology, anthropology, and linguistics.

- Educators as researchers, drawing from their professional practice

- Draw from examples of how educational researchers have identified processes in education through qualitative studies of teaching and learning. Use, as examples, the identification of the following: Culturally Relevant Pedagogy[12], Mathematical Investigation[13] and Pedagogical Content Knowledge[14].

- Educational Research as a Field

- Standpoint: Introduce the concept of the researcher’s “standpoint,” often defined as the researcher’s prior, socio-culturally constructed knowledge and beliefs that they bring to the research process.[15]

Assessment Options

- Closing Reflection: Look at students’ closing reflections for evidence of:

- Recognition of the role of decision-making.

- Valuing ethical practices by researchers.

- Recognition of the value of content analysis in the research process.

- Taking an empathetic view to researchers, including themselves.

- Instructor Reflection: Post-class, instructor reflects (memo, debriefs with a colleague, records a voice memo).

- How did students respond?

- Where did they need help?

- Where did the discussion land, and land again?

- What am I wondering about?

- Standpoint Paper (2-3 pages): A standard assignment in qualitative methods courses is for students to write a reflection paper on their standpoint in relation to a research topic. This assignment will direct students to reflect on the beliefs, knowledge and experiences (the “standpoint”) they bring to the research process and consider how they may positively engage that standpoint as researcher. [16] To assess the impact of this activity, look for evidence in students’ standpoint paper of students exhibiting empowered, reflective decision-making. Look for evidence that they will engage in reflective practices as researchers, which have historically moved the practices of qualitative research forward.

[1]Margaret LeCompte and Jean Schensul, Designing and Conducting Ethnographic Research (AltaMira, 2010); Wendy Luttrell, Qualitative Educational Research (New York: Routledge, 2011).

[2] Charles King, Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century (New York: Doubleday, 2019).

[3] William A. Firestone, Jill Alexa Perry, Andrew S. Leland, and Robin T. McKeon, “Teaching Research and Data Use in the Education Doctorate,” Journal of Research on Leadership Education 16, no. 1 (2021): 81-102.

[4] David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country – Revisited (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[5] Sam Wineburg, “Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts,” The Phi Delta Kappan 80, no. 7 (1999): 488-499.

[6] Catherine Marshall and Gretchen B. Rossman, Designing Qualitative Research, 5th ed. (SAGE, 2011).

[7] Virginia Snowden Lee, Teaching and Learning through Inquiry: A Guidebook for Institutions and Instructors (Stylus, 2004).

[8] Liza Bolitzer, Engaging Historical Thinking in Teaching Qualitative Research Methods, https://sites.google.com/view/qual-historicalthinking/teaching-activity

[9] Liza Bolitzer, “Pre-Activity Slides,” Engaging Historical Thinking in Teaching Qualitative Research Methods, https://sites.google.com/view/qual-historicalthinking/teaching-activity. See also: Aaron Cooley, “Qualitative Research in Education: The Origins, Debates, and Politics of Creating Knowledge,” Educational Studies 49, no. 3 (2013): 247-62; Robert Bogdan and Sari Biklen, “Foundations of Qualitative Research in Education,” in Qualitative Educational Research: Readings in Reflexive Methodology and Transformative Practice, William Luttrell (ed.) (Routledge, 2010), 21-44; King, Gods of the Upper Air.

[10] Liza Bolitzer, “Materials,” Engaging Historical Thinking in Teaching Qualitative Research Methods, https://sites.google.com/view/qual-historicalthinking/materials

[11] Liza Bolitzer, “Looking Form,” Engaging Historical Thinking in Teaching Qualitative Research Methods, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1r745kdCudVA9XjvpgLtpVs_xpmLf-P40/view

[12] Gloria Ladson-Billings, Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (Teachers College Press, 2021).

[13] Magdalene Lampert and Deborah Loewenberg Ball, Teaching, Multimedia, and Mathematics: Investigations of Real Practice (Teachers College Press, 1998).

[14] Lee Shulman, “Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching,” Educational Researcher 15, no. 2 (1986): 4-14. 10.3102/0013189X015002004; Lee Shulman, Teaching as Community Property: Essays on Higher Education. (Jossey-Bass, 2004).

[15] Marlene D. LeCompte and Jean J. Schensul, Designing and Conducting Ethnographic Research (AltaMira Press, 2010); Alan Peshkin, “In Search of Subjectivity—One’s Own,” Educational Researcher 17, no. 7 (1988): 17-21.

[16] Peshkin, “In Search of Subjectivity.”