by Ashley Floyd Kuntz, Florida International University

Learning Objectives

Through this historical case study, students will be able to:

- Describe the impact of the Johns Committee’s investigations on educators and students at Florida public universities from 1956 to 1965.

- Examine a single case from multiple vantage points using primary sources.

- Compare historical events to the present context for teaching, research, and administration in American higher education.

Introduction

From 1956 to 1965, the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee conducted hundreds of interrogations—first of NAACP leaders, then of educators and students suspected of being gay, and finally of faculty accused of teaching controversial texts. Led by State Senator Charley Johns, the Committee’s actions in Florida perpetuated Red Scare tactics and coincided with the lesser-known Lavender Scare to purge LGBTQ+ individuals from government employment.[1] The so-called Johns Committee interrogated hundreds of suspected “homosexuals,” often for hours in secluded locations without legal representation.[2] Given the highly sensitive nature of the allegations, the exact number of individuals impacted by the Johns Committee is unknown. However, the historical record hints at the scope. According to a 1957 memo, the Johns Committee launched investigations of nineteen junior college faculty, fourteen university faculty, 105 teachers, and thirty-seven federal employees in its first year of operation.[3] After investigations at the University of Florida, more than twenty faculty and staff were fired, and more than fifty students were expelled.[4]

By 1965, the Johns Committee became the subject of public scrutiny and dissatisfaction. The Committee lost funding, and the Governor sealed records of their work.[5] Those records were unsealed in 1992, allowing historians to explore the scope and impact of the Johns Committee’s nine-year tenure. What happened during this painful period of state history? Who resisted the Johns Committee and how did they do so? What are the implications of these events for contemporary discourse on American higher education?

Summary of Activity

This historical case study foregrounds the Johns Committee’s investigations at Florida public universities. Using intentionally sequenced learning activities, the case explores topics such civil rights, academic freedom, political interference, and other perennial issues in American higher education.

Breakdown of Activity

Pre-Class Work

Introduce students to the case by asking them to read the chapter “Margaret Fisher and Her University of South Florida Colleagues: Intellectuals versus Inquisitors” from Judith Poucher’s book State of Defiance: Challenging the Johns Committee’s Assault on Civil Liberties.[6] This source details how USF leaders prepared for the Johns Committee’s arrival and engaged in strategic acts of resistance to protect students and faculty. For example, University of South Florida leaders “invited” the Johns Committee to question suspects on campus, in the open, and with an attorney present rather than in a secluded, off-campus motel.

Divide students into reading groups to promote greater engagement with the reading and to build a common foundation for in-class discussion and active learning. Each group will summarize one aspect of the case: People (list primary actors and describe their role), Place (describe the local and state context), Plot (summarize the key events), Policies (identify and explain references to federal, state, and institutional policies), and Principles (key principles at stake in the case). Ask each group to share their summary on a collaborative virtual space (e.g., Padlet, Canvas) before class. These summaries can be used at the beginning of class to refresh students’ memories of the details of the case.

Gallery Exhibit

Prior to class, visit the case companion Google site.[7] There, you can download and print primary sources, along with a Gallery Exhibit handout. Post primary sources related to the case around the classroom like art in a gallery. The primary sources widen the aperture on the case by introducing students to the Committee’s investigations of NAACP and K-12 educators. They also document resistance to the Johns Committee’s actions.

For this activity, instruct students to visit one source at a time and complete the handout for each source they visit. Encourage students to carefully examine each source they encounter. After independent exploration, facilitate a large group discussion of the primary sources. What new information did students learn about the case? Did any of the primary sources shift their thinking? Was there a primary source that stood out as particularly valuable or important? Are there other primary sources that might have been included?

Documentary and Discussion

After the Gallery Exhibit, show the 26-minute documentary The Committee.[8] The film features contemporary narrators who describe the interrogations they endured as undergraduates at the University of Florida and Florida State University. Additionally, scholars in the film explain how Red Scare ideologies influenced the state legislature.

When the film ends, divide students into small discussion groups. Prompt them to discuss new perspectives introduced in the film that were not present or emphasized in the book chapter and primary sources. Ask them to reflect on their thoughts and feelings after viewing the film. Did the film elicit a stronger emotional response compared to the primary and secondary sources? If so, why might that be? Encourage students to consider how the medium impacts their learning. Finally, challenge students to think about how things have changed—or have not changed—since the film was made.

Connecting Past to Present

Finally, ask students to brainstorm a listing of themes discussed in the case study (e.g., LGBTQ+ oppression, academic freedom). Once they have generated a list, invite them to separate into small groups according to their interests.

In the groups, ask students to consider the relevance of their group’s chosen theme to the present context for American higher education by locating an article from a major newspaper, such as Inside Higher Ed or The Chronicle of Higher Education, that connects to their theme. How would they characterize the connection between the theme and the article they have chosen? What issues, if any, persist from then to now? What might we learn from the past to inform present actions? Each group should designate a speaker and briefly report what they discussed to the rest of the class.

Primary Sources

A complete listing of primary sources is available on the case study Google site.[9] Selected primary sources include the following:

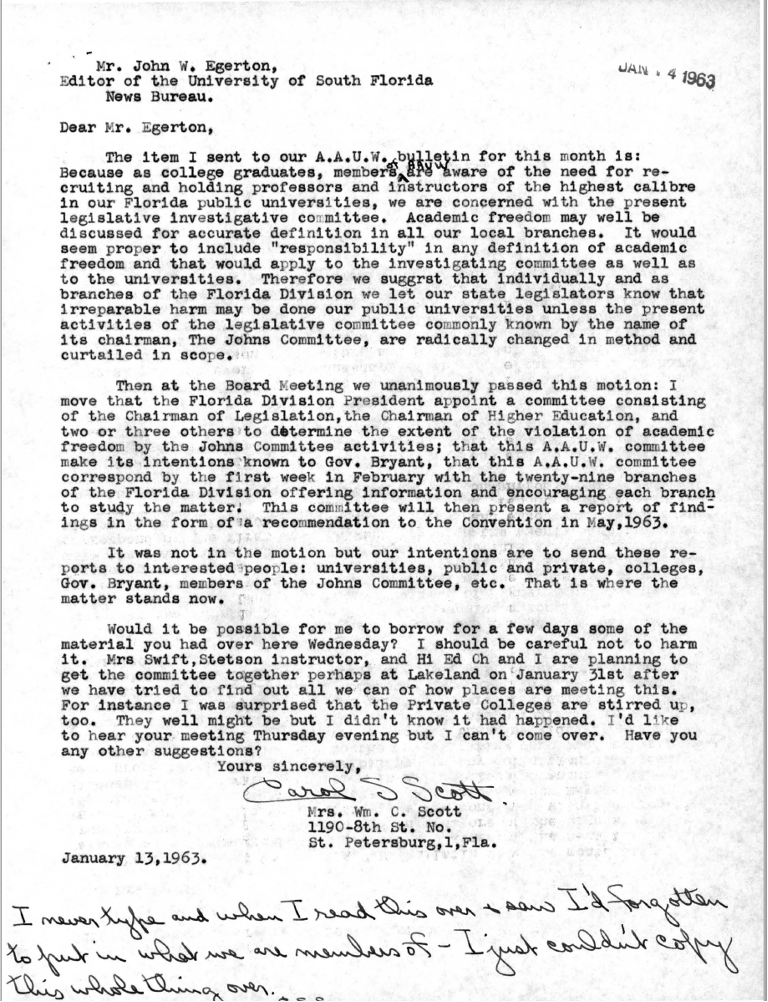

This letter from an American Association of University Women (AAUW) leader warns of “irreparable harm” to Florida’s public universities if the Johns Committee is allowed to continue the scope of its investigations. John W. Egerton, “Correspondence and Editorials Related to the Johns Committee, July 1962-April 1963)” John W. Egerton Papers,20.

Source 2

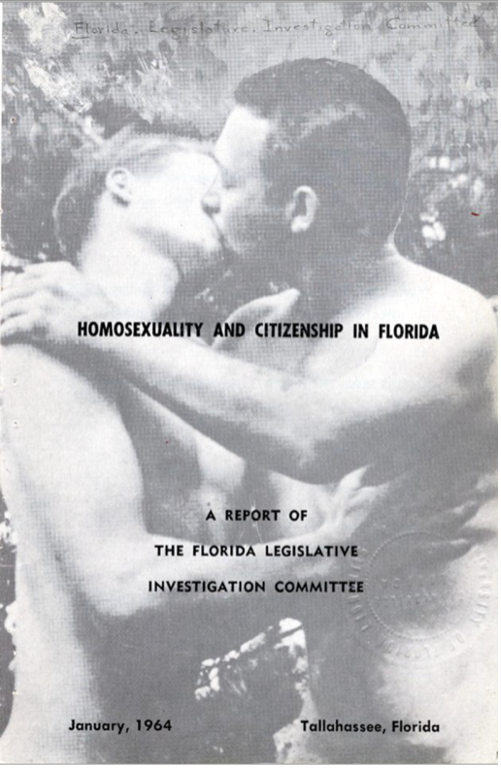

The case sources a four-page excerpt from this report. The full-length version is publicly available through the Publication of Archival and Library and Museum Materials (PALMM Collections). However, some of the images published by the state are explicit and do not add to the educational value. The sourced excerpt provides an overview of the State’s position, namely that homosexuality poses a “threat to the health and moral well-being of a sizable portion of our population, particularly our youth.” Florida Legislative Investigation Committee (January 1964). Homosexuality and Citizenship in Florida.

Source 3

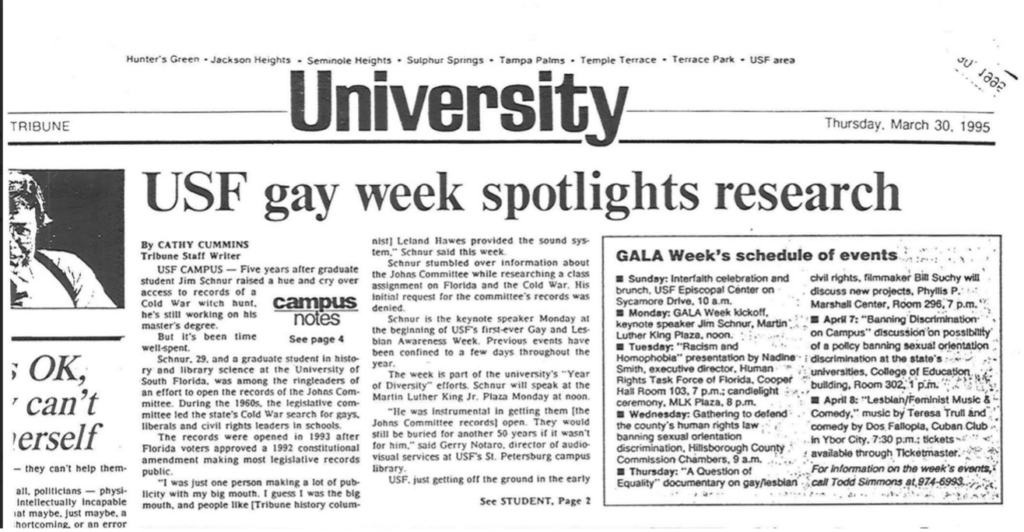

In 1992, Florida voters passed a constitutional amendment known as the Sunshine Law, which provided greater access to government records. This article describes the work of James Schnur, a master’s student at USF, who lobbied for the release of sealed Johns Committee records. Cathy Cummins, “USF gay week spotlights research.” Tampa Tribune, March 30, 1995.

Assessment Options

The following post-class assignment is designed for graduate students in higher education or college student personnel programs. The discussion prompts could be adapted to align with learning objectives in other graduate programs.

After completing the case study, assign two short discussion questions for written reflection.

- Thinking like a researcher: If you could research any issue related to this case, what would it be? Propose 1-2 research questions and identify what types of sources you might need to answer your question(s).

- Thinking like a higher education practitioner: Reflect on your response to this case study. How might what you have learned contribute to your current or future work as a higher education professional?

[1] Judith Adkins, “These People are Frightened to Death: Congressional Investigations and the Lavender Scare,” National Archives and Records Administration (2016) https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2016/summer/lavender.html.

See also James A. Schnur, “Closet Crusaders: The Johns Committee and Homophobia, 1956-1965” in Carryin’ on in the Lesbian and Gay South, ed. John Howard (New York University Press, 2012); Johns Committee Collection, University of Florida Smathers Libraries https://findingaids.uflib.ufl.edu/repositories/2/resources/1630; The Johns Committee, 1956-1965, Reference Guide, University of Central Florida Libraries https://guides.ucf.edu/glbtq/johnscommittee; USF Johns Committee Records, Digital Commons, University of South Florida https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/johns_committee/index.2.html.

[2] Robert Cassanello and Lisa Mills, directors, The Committee (University of Central Florida, 2015) https://thecommitteedocumentary.org/.

[3] Judith G. Poucher, State of Defiance: Challenging the Johns Committee’s Assault on Civil Liberties (University of Florida Press, 2014), 156.

[4] Karen L. Graves, And They Were Wonderful Teachers: Florida’s Purge of Gay and Lesbian Teachers (University of Illinois Press, 2009), 6.

[5] Poucher, 140.

[6] Poucher, 112-141.

[7] Ashley Floyd Kuntz, The Johns Committee: A Historical Case Study https://sites.google.com/view/historicalcase

[8] Cassanello and Mills, The Committee, 2015.

[9] Floyd Kuntz, https://sites.google.com/view/historicalcase